Academic Philosophy

Rawls’s Philosophical Project

I initially wrote a post explaining why I think libertarians should take Rawls seriously. But then I realized I understand Rawls pretty differently than most BHL readers. For instance, I think the Difference Principle is dispensable from Rawls’s philosophical project. You probably don’t think this. In fact, when most of you hear “Rawls” you think “Justice as Fairness” and “Difference Principle” (and “crap arguments for statism” and “hideous collectivism about natural talents”).

So in this post, I explain how I understand Rawls’s philosophical project as a whole, not just the particular manifestation of it in A Theory of Justice.

I. Operationalizing Moral and Political Conflict Resolution

I think Rawls had one, big continuous concern throughout his work, from his first major paper in 1951, all the way down through his last articles in the late 90s and early 2000s. It was to answer various versions of the following question Rawls began with in “Outline of a Decision Procedure for Ethics”:

Does there exist a reasonable decision procedure which is sufficiently strong … to determine the manner in which competing interests should be adjudicated, and, in instances of conflict, one interest given preferences over another; and, further, can the existence of this procedure, as well as its reasonableness, be established by rational methods of inquiry?

Rawls was not primarily interested, at least not primarily, in the traditional question of political philosophy articulated by Plato, “What is Justice?” Instead, he was interested in a broader normative question about how to justify rules regulating social conflicts. Rawls observed that we make lots of moral judgments across all aspects of our lives. In many cases these judgments conflict, so people make competing claims and we need some way of resolving them that all can get on board with. We need a method to resolve our disputes that all regard as reasonable and fair.

Rawls’s first insight was that this justificatory question could be answered by converting it into a question in rational choice theory. We convert the justificatory problem into a deliberative problem. In sum, Rawls’s core project is to operationalize moral and political conflict resolution.

II. Morality, Determinacy and the Difference Principle

Importantly, Rawls wanted his decision procedure to give us an account of duties, and really, moral and political obligations. So the decision procedure cannot resolve disputes by appealing to the balance of power between groups; it can’t generate obligations that way, just prudential advice about how to avoid conflict. The decision procedure must therefore be sufficiently fair.

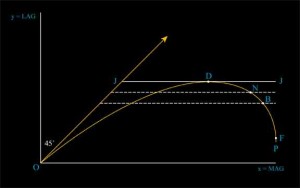

The search for a fair decision procedure led from “Outline” to Theory. Rawls realized over the course of two decades that there was no single way to solve this problem. In economic terms, Rawls saw that there were an infinite number of points on the Pareto frontier, or many distributions of wealth where all Pareto improvements had been made. So he needed a non-arbitrary method of selecting a particular point on the Pareto frontier. That’s how we got this graph from Justice as Fairness: A Restatement:

In the graph, “LAG” stands for “least-advantaged group” and MAG stands for “most-advantaged group.” J is the equal justice line, where primary goods are evenly distributed between both groups. “D” is the difference principle. It selects a distribution where the most-advantaged group has just enough primary goods to maximize the benefits of the least-advantaged. If we give the MAG less, they won’t work as hard, so they won’t maximize the position of the LAG. But if we give the MAG more, then we take from the LAG. So that’s what’s cool about the Difference Principle: it tells us the margin at which to distribute primary goods among society. So it gets us to a determinate point on the Pareto frontier.*

Rawls found the veil of ignorance model attractive because it could generate a principle of justice (the DP) that picks out a point on the Pareto frontier in a way that appears consistent with our** considered moral judgments. In other words, a sufficiently thick veil delivers determinacy. Thus, the OP is the reasonable decision procedure that Rawls had always sought. Institutions based on the two principles would resolve conflicts fairly under favorable conditions.

III. The Model and Problem of Stability

But operationalizing conflict resolution requires a further condition: the solutions generated by just institutions must self-stabilize. A fair equilibrium cannot be imposed by coercive force alone. Instead, individuals must settle on certain patterns of social behavior because they are psychologically motivated by their sense of justice to do so. In other words, the motivation to comply must come from within, based on our moral sense.

In Theory, Rawls thought it fair to assume that under favorable conditions, citizens would share enough beliefs about the human good that they would regard compliance with Justice as Fairness as a proper part of their good in basically the same way. Thus Part III of Theory.

But some time in the 1980s, Rawls realized that his model of stability was implausible. People governed by the two principles would not normally share a conception of the good or a conception of the person. Under free conditions, due to reasonable pluralism, people will tend to disagree about the good and human nature. A dynamic internal to Justice as Fairness will lead some people to reject Justice as Fairness as a proper part of their good, especially if they adopt transcendent, religious conceptions of the good, which may prioritize the achievement of spiritual goals over earthly ones. If so, then the self-stabilizing institutions of a well-ordered society would gradually collapse.

IV. The Road to Political Liberalism and Public Reason

This concern led to Political Liberalism. Rawls argued that it is more realistic to assume that reasonable people would share a conception of the citizen and a conception of society as a cooperative venture for mutual gain.

Remember: Rawls wants to operationalize conflict resolution in a moral fashion. But if reasonable people, trying to be moral, will disagree about what morality and the good require, then the decision procedure must incorporate pluralistic reasoning. That’s why we need an overlapping consensus of reasonable comprehensive doctrines: to show that Justice as Fairness, now recast as a political conception of justice, could be stable even if people disagree about their practical reasons for action.

However, once we allow for pluralistic reasoning, the stability conditions become considerably harder to realize. Since people have different conceptions of the good, they are more likely to misunderstand one another, and so more likely to doubt that others are as committed to a conception of justice as they are. Thus, we need a public political language by which we can generate assurances for one another that in fact we are on board with the same conception of justice. That’s what public reason is for Rawls. It is a moral, not legal, restriction on public discourse about constitutional matters meant to provide sufficient assurance to get people to comply with institutions governed by Justice as Fairness.

V. Disagreement about Justice

However, once Rawls made it to the paperback edition of Political Liberalism, he had to make another concession. If reasonable people can disagree about the good, surely they can reasonably disagree about justice as well. Note that this problem is worse than dissensus about the good. In cases of disagreement about the good, we still agree on a conception of justice, and so we agree on the object of stability, the set of rules we are to coordinate on despite our disagreements. But if we disagree about justice, we disagree about which coordination point is best!

Our attempt to operationalize conflict resolution has led us to multiple potential equilibria, leaving us with indeterminacy. Woe is Rawls!

Rawls argued that reasonable people will still converge on a range of reasonable liberal political conceptions of justice. These conceptions must share three features: (i) they must identify a certain set of basic liberties, (ii) assign them a special (not lexical) priority and (iii) provide all-purpose means to enjoy the worth of these liberties.

VI. Dispensing with the Difference Principle and Determinacy

NOTICE: the difference principle is not a limitation on the range. In other words, a free and equal people could coordinate on institutional rules not governed by the difference principle. Operationalizing conflict resolution in a moral manner can dispense with the difference principle. That’s why the DP is not essential to Rawls’s project.

After fifty years of searching, Rawls gave up on finding a determinate decision procedure for resolving conflicts in a moral fashion. His project unraveled on its own terms.

VII. Conclusion

So that’s how I understand Rawls. Now, here’s an obvious question: if Vallier thinks Rawls’s project fails, how can he think libertarians should learn from him? The answer, of course, is that failures are instructive. Rawls asked the right foundational questions, I think, and in the next post I’ll try to convince you of this. What I will not do is defend Justice as Fairness. That’s not the part of Rawls worth saving.

—

*Of course, it’s pretty damn obvious that the DP won’t lead a real economy to be on the Pareto frontier. But Rawls made two really implausible and indefensible empirical assumptions to guarantee that they would (see chain-connection and close-knittedness).

** The meaning of “our” changed. Initially it was supposed to include the judgments of most modern people across the world, but later Rawls restricted it to citizens of liberal democracies.