Consequentialism, Libertarianism

A Libertarian Mungerfesto: In Five Parts

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels famously wrote “A Communist Manifesto” in anticipation of an imminent earthquake in world politics. Of course, in 1848, that seemed plausible. A number of people have written some version of a “Libertarian Manifesto,” often with an analogous forecast of the eschaton for the state. (Two of the best are M. Rothbard’s effort, and D. Friedman’s effort, IMHO) I want to try something much more modest: an idiosyncratic “Mungerfesto,” with my own view of what Libertarianism might be. My experience in the “Big L” movement of libertarian politics warns me that this is more than enough to get me into trouble. So my point is that I am not speaking for anyone except myself. But I will presume to try to persuade you I’m right.  When I was a keynote speaker in 2008 at the LP National Convention, and then running for Governor in November of that year, I learned that we as a movement tend to focus on small points of doctrine as if they were the very fulcrum of our faith. Heresy and apostasy must be cleansed with fire and humiliated with criticism; infidels can be ignored. Of course, that means many of our bitterest fights are with each other.

When I was a keynote speaker in 2008 at the LP National Convention, and then running for Governor in November of that year, I learned that we as a movement tend to focus on small points of doctrine as if they were the very fulcrum of our faith. Heresy and apostasy must be cleansed with fire and humiliated with criticism; infidels can be ignored. Of course, that means many of our bitterest fights are with each other.

As I wrote over at the Freeman, it is arrogant to think that I know (and I’m implying it is ignorant to think that YOU know, my friends) just what that future looks like. (As my JB has noted, sometimes the responses to ideas are very close to religiously-framed non sequiturs.) There are some principles, however, that I think are worth talking about. And that’s what I aim to do here. So, set your flames to “Extra Crispy” and have at it!

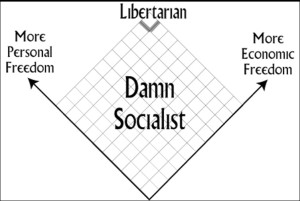

Part I: What are Libertarians? Is There More Than One “Type” of Libertarian? An old bromide tells us that there are two types of people in the world: Those who divide people into groups, and those who don’t. We, meaning libertarians, tend to be dividers. People who agree with us, on every detail, “count” as libertarians. This famous version of the Nolan Chart captures that view pretty well: 10-10 or you suck! (If you haven’t taken the quiz, here it is.) (If it matters, I’m a P9-E7).  One of the problems we face here at BHL is that the absolutist version of libertarianism, based on natural rights imperatives, is neither very persuasive to outsiders nor very satisfying to those of us who think that “social justice” cannot simply be dismissed as a category mistake. It is true enough that, as Hayek and others claimed, “justice” is an attribute of human choices and actions. But that doesn’t absolve social institutions from the requirement that the rules facilitate moral action by individuals. Quite the contrary. If you believe that incentives matter, and that individuals have moral obligations, then you should care about institutions. Some institutions are better than others. And that is really all that “social justice” means: the collective (Yikes! The “C” word!) judgments embodied in institutions and policies have moral attributes, and can be judged on moral grounds. In fact, institutions are just congealed moral intuitions, either products of conscious choice or traditions and inertia. (Wm. Riker said institutions were “congealed preferences.” I would say congealed moral intuitions, because preferences are actually harder to define.)

One of the problems we face here at BHL is that the absolutist version of libertarianism, based on natural rights imperatives, is neither very persuasive to outsiders nor very satisfying to those of us who think that “social justice” cannot simply be dismissed as a category mistake. It is true enough that, as Hayek and others claimed, “justice” is an attribute of human choices and actions. But that doesn’t absolve social institutions from the requirement that the rules facilitate moral action by individuals. Quite the contrary. If you believe that incentives matter, and that individuals have moral obligations, then you should care about institutions. Some institutions are better than others. And that is really all that “social justice” means: the collective (Yikes! The “C” word!) judgments embodied in institutions and policies have moral attributes, and can be judged on moral grounds. In fact, institutions are just congealed moral intuitions, either products of conscious choice or traditions and inertia. (Wm. Riker said institutions were “congealed preferences.” I would say congealed moral intuitions, because preferences are actually harder to define.)

In short, while it may turn out “we” can’t do some things, it is evil simply to assume “we” shouldn’t do any thing, as a “we.” There is a “we.” Homo economicus is a sociopath.

I’m clearly a member of the group that divides people into groups, because I think there is more than one type of libertarian. I think the two groups are destinationism and directionalism. The difference depends on how you reach a libertarian conclusion. The destinationist starts with two inviolable moral and ethical precepts that describe the ultimate libertarian destination, or ideal society. (a) Full self-ownership, with unrestricted rights to control and alienate both one’s own body and the products of one’s labor. (b) An absolute bar on the initiation (not use, initiation) of force, even if such force would have net social benefits in consequentialist terms. The destinationist libertarian then uses these constraints as restrictions on the form and function of the state in the ideal, ultimate sense. No violations are tolerated, no trade-offs are acceptable on consequentialist grounds.

The second group, the directionalists, are incremental, and focus on immediate policy concerns. For the directionalist, any move that increases self-ownership, even marginally, and harms no one, is an improvement. Improvements should be supported by the libertarian, according to this destinationalist perspective, even if the policy is not “truly libertarian.” In fact, it’s not clear what “truly libertarian” even means. Things are more or less, not all or nothing. Any policy that increases the liberty and welfare of one or more individuals, while harming no one, is better than the status quo. If most people are indifferent, and a few are better off, moving from the status quo to a new policy is justified for the directionalist. The directionalist, if presented with several alternatives, would want to choose that alternative that enhances liberty and welfare the most. The trick is judging political feasibility: the sweet spot is achieving the maximal increase in liberty and welfare that is possible at a point in time. How do you measure that? How would you know? More important, how would “we” know?

I admit there are problems, big ones. “Welfare”? Seriously? Look, we can talk about welfare, of a group, we just have to be careful. We have to stick to self-ownership, consent, and subjectivism. People are the only legitimate judges of their own welfare, and they have to agree, or at least agree not to object. For any given policy, an assessment requires that have to talk about it. It’s not obvious, the choices are hard, and working for change involves actual (ick!) politics and policy analysis.

To summarize:

Destinationist libertarians identify ideal policies, using ideal theory. For the destinationist, of course, anything other than the ideal outcome is an unacceptable compromise, because sanctioning a new but non-ideal status quo implies complicity. This is the “don’t vote, it only encourages them!” view of politics.

Directionalist libertarians identify a path that leads from the status quo toward ideal policies, using pragmatic and consequentialist considerations. This is the libertarian answer to the common “Tell you how you get from A to B to C” objection we hear so often. Actual, concrete policy proposals, things we could do now, and some of these policy proposals are motivated at least in part by concerns for social justice.

To close, let me admit (as is no doubt predictable) that I am a directionalist. I learn a lot from my destinationist friends, and I value your insights. You keep us all honest, and your objections are useful, because you remind us what our goals should be. But if you think that all policies that differ from your imagined libertopia are equally bad, then you are just wrong. Some non-ideal policies are much less bad than others. In the next four parts of this essay, I will try to argue for some analytical criteria for making those sorts of “less bad” incremental improvements, and make an argument for two policies that will make my destinationist friends shriek and rend their garments. Back soon…