Current Events

End the War on Drugs Now

Last week saw some truly great news: Uruguay legalized marijuana. The country is joining, and in ways now leading, what seems a growing movement towards saner drug policies around the world. In 2001 Portugal decriminalized all (!) drugs. And the Netherlands has long had a tolerant drug policy.

Ending the war on drugs is the single most important improvement we could achieve right now. No other single policy or law has results that are this terrible. And no other single policy or law could be repealed without requiring various other changes as well. We could end the war on drugs tomorrow, and things would instantly become much, much better. Or so I am going to argue.

I suppose most readers of this blog will agree with this. And I suppose that at least some of what I am about to write may be familiar. But messages that are this important bear repeating. I believe that the case I will make extends to all drugs. But even if you don’t think we should go quite that far, the arguments below should persuade you that we should at least change a lot.

(But really, we should legalize it all.)

Let me start by setting one issue aside. This is the fundamental moral argument. You might think drugs ought to be legalized because there is a principled moral case against prohibition. It’s not hard to imagine such arguments. Anti-drug laws seem clearly paternalistic, for example.

But such moral arguments are unlikely to persuade many people. They will inevitably have just enough cracks and crevices that a really determined opponent can exploit, allowing them to construct stories that, at least to them, seem just about satisfying enough.

So in this post I will not be making a straightforwardly moral argument. I will be making a prudential argument. I will show that even if you think drug prohibition is not necessarily wrong, you should still want to end the war on drugs. The reason is simple: drug prohibition is a disaster of enormous proportions, playing out right under our own noses. And the cases of Portugal and the Netherlands, and soon Uruguay as well, show that drug legalization is a much better route.

Let me put it as clearly as possible. Suppose you have a few possible drug policies at your disposal. Our current policy is one of prohibition coupled with strict enforcement. Since the early 1980s, more or less the beginning of the first Reagan administration, US drug enforcement efforts have consistently ballooned. This year (2013), the US Federal government will spend $25.4 billion on the drug war.* This leaves out state and local expenditures.

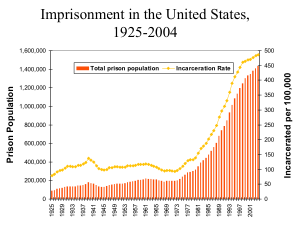

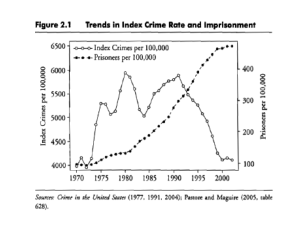

More and more people have been sent to prison over drug offenses. And by “more and more” I mean that there is no other policy or offense for which people are imprisoned at this rate. Since 1989 more people have been incarcerated for drug offenses than for all violent crimes combined.

Here is a scary chart (as with all charts below, they’ve come off rather small; you can see bigger versions by clicking on them):**

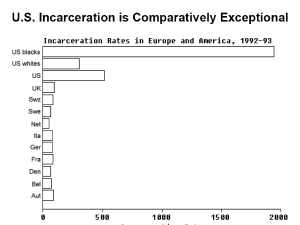

The US far outstrips any other country in incarceration rates:

This at the very least should be a source of concern. (Below, I will return to the racial disparity of incarceration. And I will mention other problems as well.) So what if there were an alternative policy as well, one that would achieve the following four things:

- Not increase addiction or pose extra risks for children

- Reduce numerous drug-related problems

- Lessen the impact of certain socially destructive outcomes

- Reduce extreme violence

Would there be any doubt – any doubt – in your mind that the alternative is better? If ending the drug war gave you (1) through (4), I simply can’t imagine how you might possibly want to keep it going.

Yet that’s the situation in which we find ourselves. So let’s go over all four points.

(1) Prohibition does not protect kids or reduce addiction

If you want drugs to be illegal, it is probably because you either fear people becoming addicted or want to protect children from using drugs. Unfortunately, drug prohibition does not seem to help on either count.

Consider first children. Monitoring the Future is an annual survey of secondary school students, college students, and young adults which measures their behavior and attitudes towards drugs. Last year (2012), when asked whether they had used marijuana in the past month, 6.5 percent of 8th graders, 17.0 percent of 10th graders, and 22.9 percent of 12th graders said they had.

That is a lot. Fortunately, though, most kids do not use marijuana. But that is not because they cannot get it. Monitoring the Future began surveying young people in 1975. Since then, the lowest number of 12th graders saying marijuana was fairly easily or very easily available was 81%. Frequently, it’s closer to 90%.

So drugs are highly available to young people. Still, most of them do not use drugs. As it turns out, they are responsible enough to choose not to.

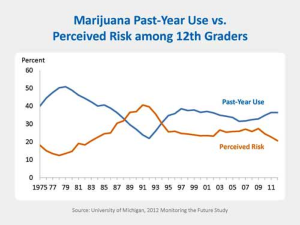

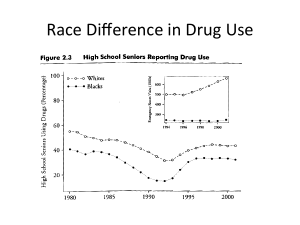

What is more, people’s use of drugs in fact does not seem very sensitive to enforcement efforts. Consider the following chart, offered by Monitoring the Future.

The standard explanation for increases and decreases in drug use refers to cultural norms, perceptions of risk, and so on. If you care about decreasing drug use among the young, you are better off trying to change their perception of drugs.

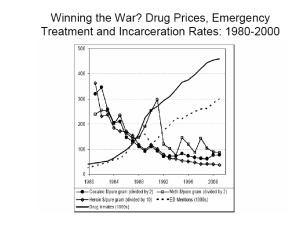

Another way of finding out whether the drug war is having results is by looking at the price of drugs. The following graph contains the prices of various hard drugs. The downward sloping lines represent the prices of various drugs. The rising line represents the number of drug inmates.

Prices are a reflection of supply and demand. If prices go down, either supply is up or demand is down. Now there is some evidence (mainly from surveys) that total drug consumption went down during the 1980s.*** But since then, the use of these drugs has remained pretty much stable. Yet prices have continued to drop. And purity levels have generally increased. This suggests that supply has significantly increased.

In fact, the chart above is a sign of relatively normally functioning market. Look, for example, at the price of meth. The spike around 1990 reflects the so-called meth-epidemic – a serious spike in demand. As you would expect under normal market conditions, supply levels responded to increased demand, driving the price gradually down.

The point: we are not keeping dugs out. Despite spending billions on it, and despite sending unprecedented numbers of people (read: mostly African Americans) to prison, we are not keeping drugs out. Basically, people who want them are not stopped by the law. At some point, the rational response is to stop trying.

But it gets worse. Suppose that the early drop in use (demand) I mentioned was indeed brought about by enforcement. Unfortunately, it has been a reduction in the “wrong” kind of use. That is, the use that has gone down has been social or recreational use. The war on drugs has had not had any positive effect on the rates or absolute numbers of addiction.

In simple terms, prohibition might prevent the occasional user, like you or me, from finding his or her way to some drugs. It does not stop anyone else. If you are a regular user, let alone an addict, prohibition will not prevent you from obtaining or using drugs.

This should come as no surprise. The same thing happened during Alcohol Prohibition. Then too, occasional drinking – like a glass of wine over dinner, a beer after work – went down. And then too, heavy drinking – the kind of drinking that tends to take place in speakeasies – went up.

A final way of testing whether the drug war helps to reduce use or addiction, and to figure out what would happen if we abandoned it, is to compare countries like the US with countries like Portugal. Since Portugal has decriminalized all drugs, the number of people who have at some point used illegal drugs has indeed slightly risen. However, it is hard to attribute this outcome to decriminalization, since the same happened in other countries in the EU as well.

More importantly, drug use in Portugal is among the lowest in the EU. And it is considerably lower than in countries with the most stringent criminalization regimes. The number of teenagers who have at some point taken illegal drugs is falling. And the number of drug addicts who have undergone rehab has increased dramatically.

So here’s the bottom line. Despite some very hard fighting, the war on drugs is simply ineffective. Of course, this might not matter if there were no real downside. But boy, is there a downside.

(2) Prohibition increases drug-related problems

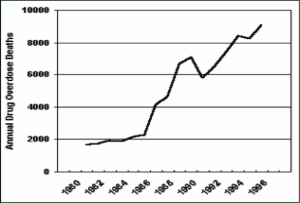

The first downside has to do with drug-related problems other than addiction. Consider the number of drug overdose deaths. Since the beginning of the drug war, overdose deaths have skyrocketed – increasing by 540% around the turn of the century, compared with 1980.

The trend has continued since.

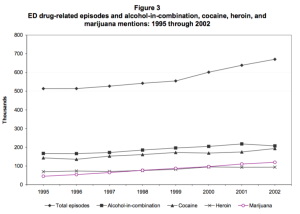

Emergency room visits involving drug overdose have gone up as well. Consider the following two charts. The first displays emergency room visits due to drug use.

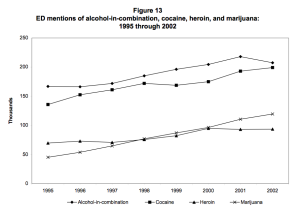

Or this chart, which reflects drug mentions in emergency rooms during the same period.

Again, the trend has continues. Between 2004 and 2009 alone, the total number of drug-related emergency room visits increased by 81% from 2.5 million to 4.6 million.****

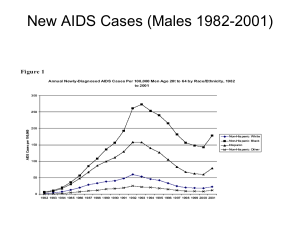

There also has been increasing numbers of HIV and Hepatitis C infections. This is mainly due to the prohibition on needle possession. As a result, addicts tend to share their of needles, leading to the spreading of HIV and Hepatitis C. Consider the chart below, which also shows how these epidemics have particularly affected African-Americans and Latinos.

There are a number of reasons for attributing these problems to the drug war (apart from the fact that their increases coincide with increased enforcement of anti-drug laws). Compare, again, Portugal, where the number of drug addicts infected with HIV has fallen significantly since the beginning of decriminalization.

Another reason for thinking this is due to the drug war is that the same processes were again visible during Alcohol Prohibition. After the Volstead Act was passed, there were rapid increases in wood poisoning, for example, a risk associated with having liquor age in poorly prepared barrels.

So the first major downside of the war on drugs is that it seems to have seriously aggravated drug overdoses, both lethal and non-lethal, and drug-related problems like HIV or Hepatitis C.

(3) The drug war has socially destructive results

The second downside is that the war on drugs has aggravated already serious social problems. Above I mentioned the increases in enforcement and incarceration since the early 1980s. The main victims of this have been African Americans.

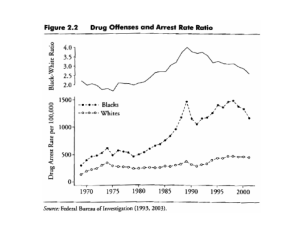

Glenn Loury produces the following graph. It shows how the war on drugs has been waged primarily on blacks.

The results have been terrible. Today, a black male resident of the state of California is more likely to go to a state prison than to a state college.

When I present these facts to people, I commonly hear that the solution is simple: black people should just stop committing crimes. But that is to miss at least part of the point. A policy that leads to outcomes that are so racially polarized is simply no good public policy.

Perhaps you think that blacks simply commit more drug-related crimes than whites? But that explanation does not pass the sniff test. It fails to explain why there is a sudden spike in black incarceration after 1980. It fails to explain why there is no similar spike for whites. And it is not clear how this fits with the fact that African Americans actually use drugs at lower rates than whites.

The real explanation is much more grim. The criminal justice system simply does not treat black and white the same. If you don’t believe me, just read The New Jim Crow and see if you still think the same. Here are but two examples. Until 2010, the ratio of the amounts needed to trigger federal criminal penalties between powder cocaine (a typically “white” drug) and crack cocaine (a typically “black” drug) was 100:1. It’s since been reduced to 18:1 by the 2010 Act that goes by the would-be-hilarious-if-it-wasn’t-so-darn-tragic name of “Fair Sentencing Act.”

Another example. Studies that compare sentencing for similar crimes but involving defendants and victims of different races have found that young, black (and Latino) males are subject to harsher sentencing, receive smaller sentence reductions for assistance, criminal history, etc., that black defendants who are convicted of harming white victims suffer harsher penalties than blacks who commit crimes against other blacks or white defendants who harm whites, that black (and Latino) defendants tend to be sentenced more severely than comparably situated white defendants for less serious crimes, and especially for drug and property crimes.

These are obviously general problems, and their sources and solutions reach far beyond issues of the drug war. Incarceration has exploded despite crime going down.

But the war on drugs is a crucial part of this story. It puts many more people, and especially African Americans, in a position where they are vulnerable to these forces. That is a real problem.

(4) The war on drugs has caused extreme violence

The third downside concerns violence. I trust I don’t have to spell out the kinds of violence in our own society caused by the war on drugs. As during Prohibition, a policy of repression takes off the table peaceful forms of enforcement and conflict resolution. And this means such issues are resolved by violence. Most people know this.

What fewer people know is the extreme violence abroad that the war on drugs has caused. The most well-known of example, of course, is Northern Mexico. Here, the effects have been truly horrific. States like Chihuahua have been basically in a state of civil war for years now. And since 2006, when Mexican President Felipe Calderón ramped up the fight against the cartels, the military has been involved in fighting drug violence. During the Calderón administration alone (2006 – 2012), the official death toll of drug-related violence in Mexico is 60,000. Unofficial counts put it more in the range of 100,000.

Those were not typos.

The drug cartels tend to decapitate their rivals, mutilate their corpses and dump them in public places to instill fear into the general public, local law enforcement, and their rivals. They control raw material production, are involved in human trafficking, and on and on and on. Corruption is rampant. Cartel members tend to give officials a choice: silver or lead (i.e. take our money or die). Entire police departments are now said to work for cartels. The same is true of the military. Instead of enforcing the law, they are enlisted by cartels to fight rivals.

There is only one way of ending this: stop the drug war. Repressing the violence through law enforcement is simply not a real option. Standard estimates of the annual earning of Mexican cartels are in the range of $13.6 billion to $49.4 billion. That’s somewhere in between the annual GDP of Jamaica or Cambodia and the annual GDP of Uruguay or Slovenia. You are not shutting that down.

The problems in Mexico are mainly due to its geographical proximity to the US. America remains the biggest consumer of drugs in the world, making Mexico the biggest site of drug transportation. Similar problems and violence occur in places that produce drugs. The drug war has created large, well-funded groups in countries where drugs are produced that have vested interests in their governments being ineffective, for example in Colombia. These groups run large-scale militias that basically rule over large portions of the country. Their presence creates a dynamic that makes peace and economic development basically impossible, as Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson chronicle in Why Nations Fail. As in Mexico, they simply stand to lose too much.

How to move forward?

What all this shows, I think, is that we should legalize all drugs. Maybe you think that is too rash. And maybe it is. But let’s not get distracted by that. There are a number of niceties we can get into about what the best policy should be. Portugal decriminalized drugs, it did not legalize them, and has tried to strengthen its drug treatment programs. Other policies are thinkable too. There is no simple dichotomy between full legalization and the disaster we have now.

All that does not remove the real point: the current war on drugs is a disaster. As I said, it is hard to think of a single other policy or law that the results of which are as bad as this one. Anything else would be a big improvement.

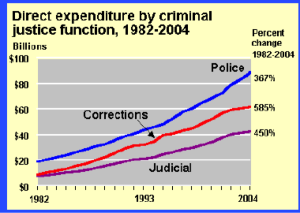

It is not going to be easy to get things changed. There now is a huge (huge) group with a vested interest in keeping this war going. More Americans are now employed in the corrections sector than belong to the combined workforces of General Motors, Ford and Wal-Mart, the three biggest corporate employers in the country. And expenditure on criminal justice functions have exploded together with the escalating drug war.

These people stand to lose from an end to the drug war. The thing is, literally everybody else has a world to win.

* About a third of this goes to treatment and prevention, the rest to enforcement, etc.

** The chart, as well as a number of others below, I borrow from Glenn Loury’s presentations here and here.

*** There is disagreement about the explanation. Some (i.e. government officials) like to claim that it was a response to increased enforcement. Others argue it had to do more with cultural changes like hippies growing old.

**** This is not just due to emergency room visits going up in general. Drug-related emergency room visits and mentions grew at roughly twice the rate of total emergency room visits.