Economics, Social Justice

The Positive Political Economy of the Basic Income Guarantee

[Editor’s Note: The following is a guest post by Josh McCabe, a PhD candidate in the department of sociology at the University at Albany and an Adam Smith Fellow at the Mercatus Center. Josh’s dissertation explores the impact of cultural categories of worth on welfare and tax politics. You can learn more about him here.]

Matt Zwolinski has caused quite a stir with his recent post arguing that some sort of basic income guarantee (BIG) might be acceptable or even necessary on classical liberal grounds. Given my background as a sociologist, I can’t contribute much to this philosophical debate on BIG or negative income tax (NIT) policies but I can speak on the political realities and prospects for introducing a BIG/NIT proposal in the United States.

Much of the discussion surrounding BIG/NIT revolves around its political feasibility and what it would look like if some country were to ever implement one. This is why those interested in the topic are keeping a close eye on Switzerland which is currently considering introducing the first universal BIG program in the world. While the Swiss case is interesting, it turns out that we don’t need to guess what some sort of program would look like in the real world. A number of countries already have active BIG/NIT programs. Am I talking about one of the Nordic welfare states? No, it turns out we simple need to look right here in the US and to our friendly northern neighbor.

The reality is that we already have BIG/NIT programs in Canada and the US. The catch is that unlike the Swiss proposal these policies are targeted at particular groups. Both countries guarantee a basic income for the elderly and disabled. In the US (aside from the state level Alaska Permanent Fund), this is done through Supplemental Security Income (SSI). In Canada, this is done through Old-Age Security/Guaranteed Income Supplement (OAS/GIS) for the elderly and various provincial programs such as the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) for the disabled.

Why have policymakers successful introduced BIG/NIT programs for these populations? In both cases, the beneficiaries in questions are not expected to work because of age or incapacity. This is consistent with explanations which focus on the legacy of the Elizabethan Poor Laws in making distinctions between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor based on ability to work. Welfare, according to many, creates dependency, saps the initiative to work, and allows the lazy to live at the expense of the hardworking. This crucial distinction is the reason social assistance programs for families with children in both countries subject beneficiaries to means-tests and invasive moral regulations. Contemporary welfare programs like Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) are associated, in the popular mind, with a range of social pathologies.

Scholars like Brian Steensland argue that this cultural legacy largely explains the failure of past BIG/NIT proposals such as President Nixon’s proposed Family Assistance Plan (FAP) in the late 1960s. An NIT program, according to Steensland, would blur the distinction between the “undeserving” poor who are employable but perceived as refusing to work and the “deserving” poor who are working fulltime and still poor and those can’t work because of age or incapacity. This would stigmatize the latter group by forcing them into the same program with the “undeserving” poor under the banner of welfare. The logic is captured nicely by this discussion between Milton Friedman and William F. Buckley.

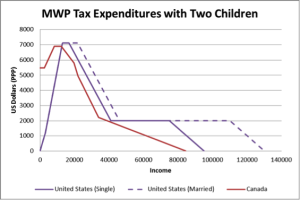

Although Steensland’s argument is, by far, the best treatment of the topic out there now, I’m not so sure it captures the full story for the simple reason that Canada already has a NIT for poor families that covers all poor and middle income families regardless of work status or employability. It’s here that the US diverges from Canada in that the US lacks a non-categorical NIT program for families. Both countries utilize what is often called “make work pay” tax expenditures in the form of tax credits. This includes in-work tax credits such as the earned income tax credit (EITC) in the US and the working income tax benefit (WITB) in Canada as well as dependent tax credits such as the child tax credit (CTC) in the US and Canadian child tax benefit (CCTB) in Canada. Both policies were introduced in response to the idea that families faced perverse incentives which favored welfare over work. While the EITC, WITB, and CCTB are all refundable, the key difference is that the CTC is only partially refundable in the US. This leads to substantial variation in the distribution of benefits in each country.

This chart excludes TANF and social assistance, both of which are available to unemployed families, because neither is guaranteed. Whereas Canada provides tax credits to families with no income, families in the US can only claim such credits if they have some minimal level of income from work. In other words, Canada has had, de facto, a substantial NIT program that makes no categorical distinctions between those who work and those who don’t for the last twenty years. This has led John Myles and Paul Pierson to label this “Friedman’s revenge” based on Milton Friedman’s early advocacy of a NIT in chapter twelve of Capitalism and Freedom. How can we explain the divergence? The existence of a NIT program for families in Canada cast doubt on Steensland’s explanation for its absence in the US. Given the common institutional origins of the American and Canadian welfare systems, it would be hard to pin this divergence on the US’s poor law legacy which Canada obviously shares as a former colony.

In my next post, I’ll explore the possible alternative explanations for why the US currently lacks an NIT program for families.