Economics, Book/Article Reviews

Schmidtz on Hayek at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

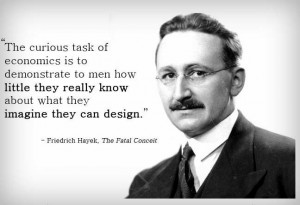

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy has a new essay up on Friedrich Hayek. This is good news.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy has a new essay up on Friedrich Hayek. This is good news.

Here’s some even better news: it is written by David Schmidtz. For those of you who don’t know, Dave is the founder and director of the Freedom Center at the University of Arizona, the author of some of the most readable and thought-provoking philosophy of the past several decades (see his Elements of Justice and the collection of essays in Person, Polis, Planet for a taste), and, most importantly, a former guest-blogger here at BHL.

Go read the whole thing yourself. It’s not your standard point-by-point comprehensive encyclopedia entry. But it’s a fascinating read that explores a number of Hayek’s ideas in ways that will often be surprising and stimulating even to those fairly familiar with Hayek’s work.

For instance, in discussing Hayek’s ideas on knowledge and the price system, Schmidtz goes beyond the familiar point that it would be impossible for a central planner to collect all of the information necessary to make efficient decisions.

A central planner could have the world’s most powerful computer, beyond anything imagined when Hayek published “Use of Knowledge” in 1945. No computer, however, could solve the problem that Hayek was trying to articulate. The problem is not lack of processing power so much as a lack of access to the information in the first place. That much seems clear enough, but the problem has a deeper level. The problem is not merely lack of access to information; rather the information does not exist. There is no truth about what prices should be, accessible or otherwise, except to the extent that prices are in fact evolving, continuously reflecting an ongoing equilibration of supply and demand.

Schmidtz also examines Hayek’s critique of social justice, a subject near and dear to us at this blog and one which I wrote about in this post, and which John Tomasi writes about extensively in chapter 5 of his Free Market Fairness. Here’s Schmidtz’s bottom line:

Hayek’s critique of social justice is more specifically a critique of centrally planned distribution according to merit. He thinks a merit czar would be intolerable. However, the nightmarish aspect of this vision has everything to do with the idea of central planning and nothing to do with the idea of merit. Anyone who takes merit seriously agrees with Hayek that it is imperative to decentralize evaluation. If Hayek is right that there is no place for a merit czar in a good society, then one could argue that, contra Hayek, the implication is not that merit does not matter but precisely that merit does matter (Hayek 1976, 64). We cannot tolerate a merit czar because a merit czar would reward obsequiousness, not merit.

Like Tomasi (and like Hayek himself), Schmidtz sees the distance between Rawls and Hayek as smaller than many have assumed.

Note the similarity between Hayek’s view and the view expressed by John Rawls in “Two Concepts of Rules” (1955). Hayek and Rawls both understood what is involved in a practice having utility. To use Rawls’s example, the practice of baseball is defined by procedural rules rather than by end-state principles of distributive justice. One has to be dogmatic (Hayek would say) about how many strikes a batter should get, in order to have a practice at all.

Imagine changing the concept of the game so that the umpire’s job is to make sure the good guys win. What would that do to the players? What would become of their striving? The result of the change would not be baseball. If we end up with a game where the umpire is making sure the favored side wins, then the players are sitting on the sidelines watching, hoping to be favored. Hayek’s insight (and Rawls’s insight at that stage of his career) is that genuine fairness is not about making sure prizes are equally distributed. It is not even about making sure outcomes are not unduly influenced by morally arbitrary factors such as how well the players played or how hard they worked to develop their talent. True fairness is about being impartial, nonpartisan—proverbially, “letting the players play.”

H/T Jim Nichols