Uncategorized

How Did the Great Recession Affect Academic Employment?

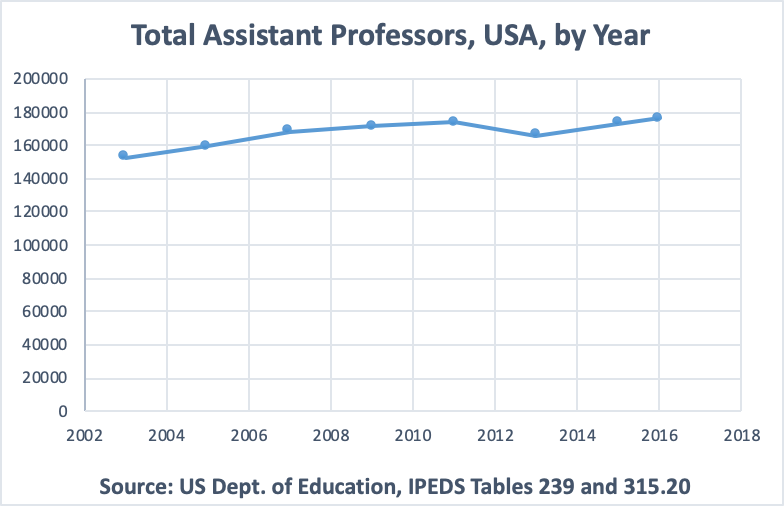

Here are the total number of people employed as full-time assistant professors in the United States over the past 20 years, according to the US Department of Education. The figure below does not include part-time faculty, adjuncts, instructors, lecturers, post-docs, or other junior jobs.

During the Great Recession, the total number of people working as assistant professors kept increasing. There wasn’t a dip until a few years after.

This is surprising, because for those of us who lived through and went on the market during that time, the conventional wisdom was that all the job disappeared. But they didn’t.

Note that if you graph the charts for full-time associate and full professors, you get basically the same shape. So, contrary to what you might have heard back in 2008, it wasn’t as if the reason there were no jobs was that the old full-timers refused to retire and thus held onto jobs that could have gone to junior people. Instead, all ranks gradually increased.

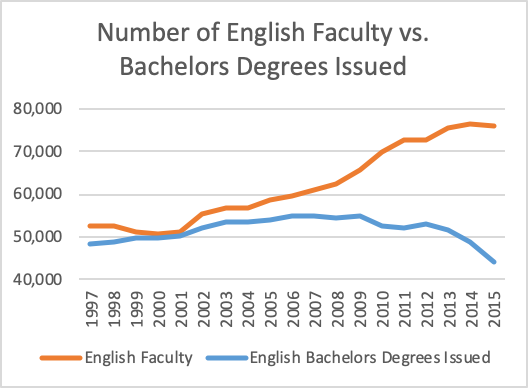

Relatedly, here’s the number of full-time faculty in English charted against the number of degrees in English. Note that this chart includes all full-time English faculty, including instructors, lecturers, and other non-tenure-track but full-time academics.

(Occupational Employment Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015; Digest of Education Statistics, Section 325)

Once you look at IPEDS and other data, you realize how dangerous it is to rely on proxies like the number of jobs listed in the MLA, or the number of horror stories published at the Chronicle. This things are misleading. People are getting jobs, and supposedly embattled English has seen explosive growth in its employment despite demand for the English degrees dropping off a cliff.

COVID-19 is different, though. While education is a countercyclical product, enrollments are likely to drop. Many students refuse to settle for online education, which provides an inferior experience. There are few randomized control trials of online education, but the few there are suggest students indeed learn less, not that higher education is about learning anyway. Second, even though students are generally a very low risk group for COVID-19 (which we now know is significantly less dangerous than most of you thought back in March, when you were writing bizarre defenses on Facebook of improper research methods), many of their parents might keep them home. Fewer students means less money in the short term means budget crises means hiring freezes and cuts. (Don’t worry. The senior assistant vice dean of administrative administration won’t lose her job, but may have to take a pay cut.) It will be interesting to see what IPEDS and BLS end up showing us about academic employment during this time.