Libertarianism, Current Events

Ron Paul: “Read The Law, by Bastiat”

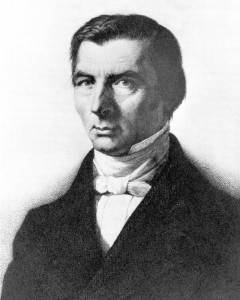

This past weekend at the Huckabee Presidential Candidate Forum, Ron Paul was asked what one book he would suggest every American read. His answer was that they should read The Law, by Frédéric Bastiat. (Video here, at about 10:40)

This past weekend at the Huckabee Presidential Candidate Forum, Ron Paul was asked what one book he would suggest every American read. His answer was that they should read The Law, by Frédéric Bastiat. (Video here, at about 10:40)

This was a great answer, and I heartily second Paul’s endorsement. If you haven’t read it yet, you should. Though Bastiat was a French economist writing in the early 19th century, his prose is still highly readable and extremely relevant. And The Law is widely available free online: HTML, Kindle, audio, and PDF versions can all be found on this page. (Those of you looking to go even deeper into Bastiat’s thought can find an immense wealth of resources at David Hart’s incredible website here)

The Law is about what legal systems should be, and how they have been perverted. The true purpose of the law, according to Bastiat, is the “collective organization of the individual right to lawful defense” of the natural rights of life, liberty, and property. But, unfortunately,

The law has been used to destroy its own objective: It has been applied to annihilating the justice that it was supposed to maintain; to limiting and destroying rights which its real purpose was to respect. The law has placed the collective force at the disposal of the unscrupulous who wish, without risk, to exploit the person, liberty, and property of others.

Instead of protecting our rights, the law has turned to plundering them. The main causes of this plunder, in Bastiat’s eyes, are two: “stupid greed and false philanthropy.”

Bastiat’s discussion of the role of greed in promoting plunder is especially relevant today, given ongoing concerns about corporatism and its relation to capitalism as expressed by both libertarians and certain segments of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Bastiat presents a clear and simple diagnosis of the root cause of corporatist plunder:

When they can, they wish to live and prosper at the expense of others … Man can live and satisfy his wants only by ceaseless labor; by the ceaseless application of his faculties to natural resources. This process is the origin of property. But it is also true that a man may live and satisfy his wants by seizing and consuming the products of the labor of others. This process is the origin of plunder. Now since man is naturally inclined to avoid pain—and since labor is pain in itself—it follows that men will resort to plunder whenever plunder is easier than work. History shows this quite clearly. And under these conditions, neither religion nor morality can stop it.

How can we identify and stop plunder?

Quite simply. See if the law takes from some persons what belongs to them, and gives it to other persons to whom it does not belong. See if the law benefits one citizen at the expense of another by doing what the citizen himself cannot do without committing a crime. Then abolish this law without delay, for it is not only an evil itself, but also it is a fertile source for further evils because it invites reprisals. If such a law—which may be an isolated case—is not abolished immediately, it will spread, multiply, and develop into a system.

And in Bastiat’s time, he saw that plunder had developed into a system, where any merchant, guild, or special interest with the resources to do so would struggle to gain influence or control over the coercive power of the state in order to twist it to serve its own private ends. The result: a system of universal plunder sustained by the “delusion” that the the law can be made to “enrich everyone at the expense of everyone else.”

Not all plunder, however, has its origins in nefarious motives. Some has its origins in a genuine desire to help the less fortunate. And Bastiat was one who believed that charitable aid to the poor was an important virtue. But the purpose of the law is justice, not charity. And to use the law to achieve charitable ends inevitably perverts justice.

You say: “There are persons who have no money,” and you turn to the law. But the law is not a breast that fills itself with milk. Nor are the lacteal veins of the law supplied with milk from a source outside the society. Nothing can enter the public treasury for the benefit of one citizen or one class unless other citizens and other classes have been forced to send it in.

Such a view might appear cold-hearted – suggesting that the needs of the poor are of so little moral weight that they cannot justify even the most trivial infringement on the liberties of the well-off. Does Bastiat think that society has no obligation to the least well-off? No. This charge, says Bastiat

confuses the distinction between government and society. As a result of this, every time we object to a thing being done by government, the socialists conclude that we object to its being done at all. We disapprove of state education. Then the socialists say that we are opposed to any education. We object to a state religion. Then the socialists say that we want no religion at all. We object to a state-enforced equality. Then they say that we are against equality. And so on, and so on. It is as if the socialists were to accuse us of not wanting persons to eat because we do not want the state to raise grain.

Bleeding Heart Libertarians like myself might take issue with some of Bastiat’s claims about the defensibility of social justice and the exact nature of a state’s obligations toward the poor. But even if you don’t agree with him 100%, you’re sure to find much in The Law to enjoy, ponder over, and admire.